|

|

| HISTORY |

|

THE MOUNTAIN ROUTE

The first trip across the Santa Fe Trail was made with pack animals and traveled over what eventually became known as the Mountain Route. Raton Pass, however, was too rugged for heavily loaded wagons, so for the next twenty plus years, traders taking wagons to Santa Fe skipped this route and created a shortcut across the prairie along the Dry Cimarron River. The Cimarron Cutoff, as it was named, became more and more dangerous over the years, so people once again looked to the Mountain Route.

With a little dynamite and a lot of hard work, a private toll road was constructed over Raton Pass and the Mountain Route quickly became the safest, and the favored, path for Santa Fe Trail traffic. Even though it was a longer route and required 5 extra days just to cross the still-brutal Pass, the Mountain Route offered a steady supply of wood, water, and grazing. It also passed through terrain occupied by mostly peaceful Indians. It took about 72 days to make the trip across the Mountain Route.

By the time the Mountain Route became popular, very few individuals still pulled wagons across the plains in search of their own private fortune. By the 1850s, big freight companies and professional teamsters were hauling most of the freight on the Trail and much of that freight was headed for the giant warehouses at Fort Union. Racing against the clock was no longer as critical as it was in the early years. The safe crossing for men and cargo justified the $25 toll and the extra 10 days this route added to the crossing.

Because it was safer, the Mountain Route was also a favorite stagecoach route. A stagecoach could make the journey from Missouri to Santa Fe in 25-30 days.

Raton

Raton sits where towering mesas, beautiful alpine valleys and the Great Plains all meet. Wagon trains passing through on the Santa Fe Trail only found a meadow here, with a spring where teams and teamsters alike could prepare for, or recuperate from, the crossing of the treacherous Raton Pass. Eventually a ranch house was built at the spring and a stagecoach stop, the Clifton House, was built several miles to the south.

As the railroad was slowly dooming the Santa Fe Trail, it was giving birth to the town of Raton. Before you knew it, Raton was awash with culture, capitalism and cowboys. Many of Raton's beautiful old buildings still see daily use. The dirt streets and hitching posts are gone, but downtown Raton still holds its historic charm. The grand old Theater is still open for tours and frequently hosts evening entertainment. The one hundred year old Coors Brewing Co. building now houses the Raton Museum.

The railroad and agriculture have always given Raton its public image, but for over a hundred years coal mining helped build Raton. The Raton Museum is a good source for pictures and stories of the history of coal mining here.

Ghost Towns

Raton is literally surrounded by ghost towns that were once coal camps (mining towns). As you drive on the Scenic Byway between Raton and Cimarron, you will pass to the east of the most tragic of them all, the once sizeable city of Dawson. A hundred years ago, Dawson was on its way to being an ultra-modern mining community. Dawson, which was considerably larger than modern-day Raton, supplied an area 1/6th the size of the United States. For a coal town, the accommodations were elaborate. These accommodations included a golf course, opera house, bowling alley, hospital and even a public swimming pool.

Tragedy, however, was in the cards for Dawson. In 1913, only two days after a successful safety inspection, the countryside rumbled from an explosion deep within the earth. Wives, children and fellow miners waited breathlessly, and in vain, for 263 loved ones to emerge from the smoke. It was the second worst loss-of-life accident in coal mining history. Ten years later, widows of the first accident would repeat the scene, this time praying that their sons survived. Of 123 men working the shaft that day, only two men made it out alive.

The mine remained in operation for 3 more decades, but it was almost as if the memories were just too painful to overcome. When the mines were closed, the entire city was nearly erased from existence; the properties were bulldozed and restored to ranch land.

Today, more than 350 white iron crosses mark the graves of those who died in the mines. They are nearly the only remaining evidence that this wonderful, yet so terribly tragic city ever existed.

Cimarron

Don't let Cimarron deceive you. It would have you think it was always a quiet, respectable frontier town, when in fact, it was among the wildest of the towns in the West.

A gold strike in the mountains to the west, as well as the end of the Civil War, brought a lot of single men to Cimarron. The Santa Fe Trail added a steady stream of teamsters - single men who for two months had seen neither saloons nor women. Fort Union contributed a bunch of young, off-duty soldiers, including soldiers from the black regiment who were bitterly resented by the ex-confederate soldiers. Add all of those to the typical numbers of antisocial cowboys and gunslingers and you see why Cimarron was different. If you can imagine giving all these young, rowdy men some poker tables, saloon women, and all the alcohol they could drink, then you can probably imagine Cimarron late in the 1800s. As small as it is, at one time Cimarron sported 16 saloons.

Here ruffians rode their horses into saloons and in drunken celebrations rode through town whooping and hollering while shooting out windows, lanterns and just about everything else. Gunfights and outright murders were nearly a daily event. When a sheriff was hired to put an end to this nonsense, Davy Crocket (either a nephew or grandson of the famous frontiersman) forced whiskey down him until the sheriff literally passed out. Gunslinger Clay Allison shot at his feet to make him dance. That was Cimarron before things really got rough.

To make a long story very short, a Dutch company bought the whole area out from under residents and put together a ruthless organization to try and clear the land of citizens and squatters. They had chosen a bad place to pick a fight. The Colfax County War resulted and ended up costing the New Mexico Governor his job and around 200 people their lives.

Today Cimarron is a peaceful and even quaint little town. It is small enough that people are still personable, the food is good and the gift shops are great. But as you walk the streets and peruse the shops, remember that it hasn't always been this way. Even the name, "Cimarron" means "wild".

St. James Hotel

Undoubtedly the most famous of the buildings in Cimarron is the St. James Hotel. Even though it hosted plenty of rough customers, it was an upper class establishment and a very popular place to be. Like the rest of Cimarron, the Saint James saw its share of gunfights. It is thought that 26 men were killed within the saloon and hotel. When the roof was replaced in 1901, more than 400 bullet holes were counted in the wood planking under the roofing.

The hotel and saloon had some guests of considerable notoriety. Author Zane Grey wrote here, and Governor Lew Wallace is rumored to have stayed here while writing a portion of his epic story Ben Hur. Frontier artist Fredric Remington sketched the nearby hills, and Buffalo Bill Cody met with Annie Oakley here to plan his Wild West Show. Train robber Black Jack Ketchum, Jessie James, Poncho Griego, Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, Clay Allison, General Sheridan, and Kit Carson are all rumored to have bellied up to the bar or bedded down here. Numerous stories of resident ghosts and more than twenty still-visible bullet holes in the ceiling add to the mystique of this nicely preserved hotel.

Just west of the St. James you will find the town's grist mill. For a hundred and forty years it has been witness to the history of Cimarron and now it is a museum that helps tell Cimarron's story. It is filled with nice artifacts and photos of our frontier past.

There are other interesting sights and buildings which have survived the years, including the old jail house. Be sure to stop in at the Chamber of Commerce/Visitors Center and get detailed information on the walking tour. Plan on spending some time in Cimarron; it is the real thing.

Maxwell Land Grant

Spain wanted to establish these lands as an extension of Spain itself and badly needed people to build communities and to govern on the King's behalf. Rather than pay massive sums of gold to accomplish this, Spain offered sizable estates to capable Spaniards willing to relocate here. The New World contained an abundance of land and giving away large land grants was a small price to pay in order to lure capable people to the primitive, distant lands.

Under Mexico's rule, land grants were continued and even given to foreigners who were thought capable of governing or from whom favors were desired. The largest land grant ever awarded was right here surrounding Cimarron. The Maxwell Land Grant was around 1.8 million acres, an area roughly the size of Ireland. It is called the Maxwell Land Grant because it wound up in the hands of a single man, Lucien Maxwell, and it made him the largest landowner in the western hemisphere.

It is only fitting that what was once the biggest single parcel of land now supports the world's largest camping facility (Philmont Scout Ranch) in one corner and the world's largest single buffalo herd in another. Unfortunately, unless the buffalo wander close to the highway north or east of town, you rarely get to see much of the herd. The Philmont Scout Ranch is easier to find and even if you are not interested in scouting, you will find their museums interesting and the Villa Philmonte a very worthwhile stop.

Rayado - Philmont

Not all wagons on the Santa Fe Trail were destined for Santa Fe. Traders could make serious profits on their goods in other communities too. Some wagons passed right through Santa Fe and journeyed all the way to Mexico City. Taos was also a popular destination for many of the wagons coming out of Missouri.

Where the trail to Taos crossed the Santa Fe Trail, Lucien Maxwell built the town of Rayado; the first Mexican settlement east of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Rayado is located in the strikingly beautiful land just south of Cimarron; much of which is owned by the Boy Scouts of America. Even if you have no interest in scouting, the Philmont Scout Ranch is worth a visit. The Scout Ranch is more than just heaven to a Boy Scout; it is a massive facility that includes some of the area's most beautiful mountains, valleys, and historical sites.

Kit Carson built a home in Rayado that has been restored and is now part of a museum operated by the Scouts. During the summer months, the scouting organization presents a living history exhibit with a blacksmith shop, a noon meal cooked on the patio, and black powder demonstrations.

They also maintain other treasures including the personal residence of the land baron Lucian Maxwell, and the summer home/mansion of oil baron Wade Phillips. Be sure to stop at the Scout Ranch on your drive to Rayado.

Fort Union

In the 1800s, 4 out of 5 members of the US Cavalry were stationed in the West and Fort Union was the largest fort in the Old West. One part housed soldiers protecting settlers and the Santa Fe Trail. Another part housed ordnance, where artillery and weapons of all kinds were stored and distributed to the other forts. The biggest portion of Fort Union was the Quartermaster Supply Depot, which served as the warehouse and distribution point for nearly 50 other forts throughout the West.

For wagons that had just crossed the prairie, Fort Union was like an oasis in the desert. For travelers with injuries or disease, Fort Union had the first modern hospital they would encounter since entering the prairie. Strangely enough, in the 1800s it was widely believed that traveling the Santa Fe Trail would cure people of all sorts of medical conditions, so a lot of sick people traveled in coaches accompanying wagon trains. Even without these people, all types of injuries and illnesses were common including fever, snakebite, diarrhea, cholera and malaria. Wagons also took a beating on the Santa Fe Trail and many came limping in to Fort Union in desperate need of attention. The blacksmith's shops were a welcome sight.

The soldiers at Fort Union numbered in the hundreds, but it took thousands of people from surrounding communities to keep the Fort going. Fort Union was a boon to the region's mostly Hispano communities. Thousands of wagons arrived at Fort Union each year with millions of dollars in goods. Local citizens were hired to do many laborious tasks involving both the incoming and outgoing freight as well as maintaining the facilities.

Fort Union bought most of its perishable supplies from the surrounding communities creating a boom for locals raising everything from wheat and vegetables to lumber and beef. Flour mills sprang up throughout the region to keep up with the supply demands.

Curiously enough, Fort Union wasn't enclosed by a wall. Private forts like Bent's Fort and Fort Barclay had fortified walls, but those forts were more subject to attack. In old photographs of Fort Union, you see picket fences enclosing a big portion of the Fort's massive perimeter.

When the Fort was abandoned over a century ago, a great deal of the building materials were recycled (or looted, depending upon your perspective) to build homes in surrounding communities. When you visit Fort Union, you will see more foundations and fireplaces than intact buildings, but it is still worth the visit. The Visitor Center has the whole story presented in a nice facility by friendly people. Watch the film and you can more appreciate the Fort. Then stretch your legs by walking the one-mile trail out onto the breezy prairie that many a lonely soldier called home. It is time well spent.

MORA RIVER VALLEY

The Santa Fe Trail was really more of a corridor than a trail. Unlike today's roads and right-of-ways, the Santa Fe Trail changed a lot. Mother Nature forced some changes to the Trail as watering holes dried up and floods washed out river crossings. Traders were also tempted to find every shortcut possible because their goods were much more valuable if they arrived in Santa Fe before competing wagon trains saturated the market. Over its nearly 60 years of existence, the Santa Fe Trail had produced many little variations to its body. Each of these little variations, however, eventually joined back up with one of the two principle routes, either the Cimarron Cutoff, or the Mountain Route. Eventually even these two routes came back together to form one Santa Fe Trail. For wagons headed to Santa Fe, that junction happened at the town now called Watrous. During the 1800s, Watrous was called La Junta and was a hub of Santa Fe Trail related activities.

Watrous

Wagon trains were like a parade; anyone interested in participating had to pack their wagons and meet at a designated location called a "jump-off point". When it was generally agreed that there were enough wagons (and guns) to safely venture out across the plains, a Wagon Master was elected and off they would go. If someone arrived at the jump-off point after the wagon train was already gone, they had to wait for other wagons to arrive and form the next wagon train. Watrous was the jump-off point for caravans forming up for the trip to Missouri.

Watrous sits at the junction of two rivers, the Sapello (sap-ee yoah) and the Mora. Because Watrous was also located at the junction of the Mountain and Cimarron Routes of the Santa Fe Trail, it was the perfect place for a fort or two. Alexander Barclay built a privately owned trading fort at the west edge of Watrous, and the US military built the mammoth-sized Fort Union just to the north.

In addition to the normal variety of saloons and hotels that thrived in frontier towns, the Barlow-Sanderson Stage Line built a stagecoach station that still stands today. A big part of the old saloons, hotels and businesses in the downtown section of Watrous burned in 1910, just a few years after a flood turned Fort Barclay into a mound of dirt in an open field. Fort Union has been made into a national monument and is well worth a visit.

The 150-year-old house of Samuel B. Watrous still stands on the north end of town and appears untouched by time. His house contained a store that catered to wagon trains on the Santa Fe Trail until the railroad came through and ended the need for the Trail. It is not open to the public but is easily visible from the road.

When the railroad came to town, Santa Fe Trail traffic died, but business at Watrous picked up as it became a large shipping outpost for lumber. Trees were hauled from the mountains to be sawn and loaded on trains at Watrous, most likely to support the ever-expanding railroad line and to build the rapidly growing city of Las Vegas. Watrous is considered a ghost town, though residents would argue that point. The town has some interesting old buildings and a good book on ghost towns or a chat with a resident there might help you identify those buildings.

Mora River Valley

The Mora River Valley is significant for a number of reasons. For centuries, the Mora River Valley was used as a pathway from the plains into the mountains. It is claimed that the first white Europeans to cross the plains from the East, followed the Mora River Valley into the mountains on their way to Santa Fe. It, however, had been a busy thoroughfare for centuries.

Over the centuries, this stretch of the Mora River Valley has seen an unprecedented variety of history. Jicarilla Apaches used to live here as evidenced by the circles of dead earth called teepee rings. There are fire pits on some of the surrounding mesas that purportedly housed fires for smoke signals.

Conquistadors passed through here with their huge entourage of soldiers, servants, priests and herds. Mexican soldiers passed through here as they provided protection for local wagon trains headed across the Santa Fe Trail to America. Years later, American soldiers rode by here as they claimed New Mexico for the US. The cliffs lining this river valley provided cover for the rebels who fought against the US occupation. Rebels hid out in this very valley while carrying out raids against American interests. For many hundreds of years, both Mexican and Indian buffalo hunters passed through here headed far out onto the plains in search of buffalo.

From this same vantage point you could have seen the migrant (Chinese, Black, Irish and Hispanic) workers as they buried the cross ties and drove the spikes of the very first railroad built into this land and heard the whistle of the first steam engine to penetrate this deep into what was to soon become the next addition to the Wild West. You could have seen the French Canadian trappers as they passed through attempting to smuggle their illegally trapped beaver out of the mountains of Mexico and sell them to traders who were headed back to Missouri. You could have seen the desperados and gunslingers who rode the railroad on their way to gamble in Las Vegas and seen the Comancheros who maintained hideouts in these canyons as they carried out their sinister dealings with the Comanches.

You could also have watched as dragoons, teamsters and cowboys headed up this valley to Loma Parda for a wild night of gambling and drunken debauchery or seen the convoys of wagons hauling logs from the mountains to be cut up and shipped in Watrous. You could have heard the intolerable screech of the two-wheeled Spanish style carts loaded with wool and hides and seen the pack trains of mules carrying buffalo hides as they all headed for markets in Missouri. This Valley has seen an incredible amount of history.

Sodom on the Mora

This was the nickname given to what started out as a respectable and even peaceful little village on the Mora River a few miles upstream from Watrous. It began as a town of hard-working Hispanos who raised sheep and crops and fought all the hardships of life in the New World. For generations they survived drought, floods, and attacks by Indians and endured the extremes of heat in the summer and deep snow in the winter. They were hard-working and decent people. Unfortunately, that is not what they will be remembered for. Now essentially a ghost town, Loma Parda was forever changed when Fort Union moved into the neighborhood.

Loma Parda became the town where soldiers could go for wild nights. Saloons, gambling, dance halls and women of ill repute put Loma Parda on the map; especially if you were a soldier bored with your isolated existence at Fort Union. When a soldier went AWOL, it was half expected that he was still at Loma Parda either passed out or just too drunk to know where he was. Not all drunken debauchery was on account of the soldiers though; cowboys and teamsters from the Santa Fe Trail engaged in their share of the mayhem.

It was in the streets of Loma Parda that a cowboy on horseback grabbed a lady in the street, pulled her across the saddle in front of him, and rode his horse right into the saloon where he demanded that the bartender serve drinks to everybody. Then, when his horse would not drink, he pulled his revolver and shot the horse through the head. He retrieved the lady and left his dead horse on the saloon floor.

Loma Parda had a reputation it would never live down. It has a fair number of rock walls still standing, and is considered a ghost town, even though it is still occupied by a few souls. Once a vibrant community tucked down in this magnificent river valley, it was a place where legends were made.

New Mexico's Breadbasket

The local Indian Agencies, the Santa Fe Trail traffic and the military forts in the region needed massive supplies of wood, meat, vegetables, grains and flour. The Mora River Valley had long been a fertile agricultural area, but residents here had traditionally grown just what they needed to survive. With the arrival of the Americans and the Santa Fe Trail, residents here took to raising crops for profit.

With the sudden demand for massive quantities of ground wheat flour, many big new flour mills began to spring up. French, German and Jewish immigrants took well to the industry and were credited with building many of the wheat mills in the area. From Mora to Watrous, the Mora River Valley became the breadbasket of New Mexico. Several old mills still survive and can be seen in the Valley above and below the town of Mora. Of particular interest is the roller mill in Cleveland that has been restored to working condition and made into a museum.

Spanish-style villas were usually built around a plaza which had a community well and was surrounded with land shared by the villagers for raising livestock and crops. The land was more suited to raising sheep than cattle, so most settlers here either farmed or kept sheep. Life for early Spanish and Hispano settlers was very difficult. The average lifespan was 47 years. Droughts were common, Indians frequently attacked settlements, and the unfortunate effect of many Spanish laws and governors seemed to conspire to keep villagers poor.

Prior to the Santa Fe Trail days, people here mostly wore clothes made from leather and had to build their own homes and farms without the benefit of tools, including plows, saws, or even nails for construction. Villagers had to make everything they needed. If they couldn't make it, it wasn't available.

Mora

Mora is the home of the fictional Sackett family in the famous western series written by Louis L'Amour. The real town of Mora occupies an absolutely beautiful valley surrounded by magnificent pine-and-aspen-covered mountains.

Even though Mora wasn't situated on the Santa Fe Trail, journals written by travelers on the Santa Fe Trail did mention Mora on occasion. Traders, anxious to get the best prices for their goods, may well have made the detour here to sell items before continuing on to Santa Fe. Since the official Port of Entry was further down the Trail, traders may have used this opportunity for some untaxed profit-taking. Whatever their reasons, many traders reflected favorably on their visits to Mora and wrote of the traditional Spanish customs and fandango dancing.

When the United States claimed this land from Mexico, most residents surrendered without a fight. Not everyone was happy about that development, though, and resentment in Mora and Taos spiraled into an outright rebellion. In Taos, the Governor of New Mexico was murdered in the revolt. In Mora, Santa Fe Trail traders were killed in the uprising.

We don't know as much about Mora during this time as we could because much of its early written history was destroyed. To put down the rebellion, US soldiers surrounded the town of Mora and using artillery fire, literally flattened the town. Buildings that survived the shelling were burned. The town of Mora never fully recovered. The town may have been destroyed, but the spirit was never defeated. The people in Mora are friendly, but to this day Mora has a reputation for standing its own ground, living by its own rules, and determining its own fate.

Besides its beautiful valleys, Mora has some interesting attractions. At Victory Ranch you can see and pet real alpacas in one of the largest alpaca herds in the US. Weaving has been a cottage industry here for nearly 400 years and you can still buy hand-made textiles, made in the traditional styles, from Tapetes de Lana, the nonprofit distributor for local artisans. You can also pick your own fresh raspberries at the Salmon Ranch, or witness history as the roller mill at Cleveland makes flour the old-fashioned way. Mora has great hunting, fishing and hiking in just about every direction you want to go, and for good-home style cooking, Mora has some small but excellent restaurants all up and down the valley.

SANTA FE - LAS VEGAS CORRIDOR

The serene and quaint atmosphere that cloaks today's Santa Fe, belies the horrific upheavals it has experienced. Those who survived to call this land home were extremely resilient, resourceful, and probably a little bit lucky. Through it all, though, Santa Fe has found a sense of tranquility that comes with age and that peace adds much to Santa Fe's charm.

The land around Santa Fe is rich with petroglyphs, cliff dwellings, ruins and other evidence that people have lived here for many thousands of years. It is thought that the Pueblo Indians arrived here around seven hundred years ago and the Apache, Comanche, Navajo and Ute came soon after.

Spanish conquistadors first came to New Mexico about 500 years ago. In 1610, they established the city of Santa Fe. Many of those original Spanish buildings still see daily use.

By American standards, the city of Santa Fe is old. Santa Fe was the capital city for everything west of the Mississippi for a century and a half before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It is the oldest continuously-occupied capital city in the United States. Many in Santa Fe claim it has the oldest home and oldest church. It certainly is true that Santa Fe has the oldest official government building - the Palace of the Governors. The palace of the Governors is older than the Taj Mahal.

Nearly 400 years ago, the Palace of the Governors was built for the specific purpose of housing the seat of government in Nuevo Mexico and it served in that capacity for 300 years. For nearly a century now, it has served as the official Museum for the State of New Mexico.

The Palace takes up the entire north side of the Historic Plaza in downtown Santa Fe. That town square was the end of the line for wagon trains coming over the Santa Fe Trail. Wagons loaded with goods would fill the square in front of the Palace while hoards of locals crowded around to celebrate the arrival of the wagons and to begin the joyful task of haggling over much-needed merchandise. Traders found a warm reception, a populace with money to spend, and a dire need for goods. The arrival of wagons was a cheerful event for buyers and sellers alike.

It is not possible to describe here the many worthy experiences that Santa Fe has to offer. Begin your trip at the Visitor's Information Center where you will find resources for exploring Santa Fe. But plan on slowing down and experiencing Santa Fe the way it should be, relaxed and peacefully.

Apache Canyon - Glorieta Pass

As you leave Santa Fe to follow the Trail eastward, you won't travel far before you get to your first historically significant stop on the Santa Fe Trail. As you drive through the narrow straits of Apache Canyon, you pass through a series of Civil War battlefields. The battles that took place here affected the outcome of the Civil War.

The Confederate Army wanted to capture the gold from the recent strikes in Colorado and in California to finance their war back East. With the spending power of that gold, the leadership of the South may well have been assured victory.

The first shots had hardly been fired back East before Confederate troops had entered New Mexico from the south. Troop strength was down at Union forts and most of New Mexico fell to Confederate control quickly.

Just as in the East, Confederate forces were having success everywhere they went. To the north of Santa Fe, though, commanders at Fort Union struggled to change that. With reinforcements by volunteers from Colorado and Utah, Union troops were determined to stop the Confederate advance before it reached Colorado. Using the steep canyons to their advantage, they engaged the Confederate military right here in the narrow straits of the Glorieta Pass and dealt the Confederate Army their first loss of the Civil War.

Confederate officers had gambled that the sheer rock walls of Apache Canyon would be sufficient to assure the safety of the wagons carrying their food, supplies, and ammunition. They were wrong. As the Confederate soldiers were winning the battle raging in Glorieta Pass, a group of volunteer forces snuck around the battlefield, scaled down the face of the cliffs, and destroyed the supply wagons. They bayoneted the mules and burned the wagons. Until now the Confederate forces had won every encounter they fought, but without supplies and ammunition, they had lost the ability to continue their campaign.

Confederate forces were forced to retreat across hundreds of miles of a very hot and dry land. The trip devastated the surviving troops. By the time they returned to Texas, neither officers nor soldiers had the strength or the will to try again. The brief Confederate occupation of New Mexico was over.

The Civil War conflicts were fought all along the Santa Fe Trail where it passed through Johnson's Ranch, Glorieta Pass and the stage stop at Pigeon Ranch.

Pecos

It is thought that the Pueblo at Pecos was built by the Anasazi people around 600 years ago. The Pueblo Indians had occupied the Pueblo for around two hundred and fifty years before the arrival of the Spanish, and did so for another three hundred years after that. The Pueblo people were great hunters, but are remembered most for their farming skills, their architectural wood carving, and their success at trading. Both Jicarilla Apaches and Comanche engaged in trade at the Pecos Pueblo.

It wasn't long before the first mission was built. Unlike the rest of the structures in the Pueblo, it was built using adobe instead of stone. It was a large and impressive structure, but was destroyed during the first Pueblo uprising.

When the Spanish came, they enslaved Native Americans, including the Pueblo Indians. Spanish priests were brought to convert the Pueblo people, which meant taking away their native language, customs and religion. On two different occasions, the Pueblo Indians rebelled against the Spanish. On both occasions, people of surrounding Pueblos staged bloody revolts where Spaniards were killed or driven out. The first mission at Pecos did not survive the first Pueblo revolt, and the damage you can now see to the fourth mission was partially the result of the second uprising over a hundred years later.

Amid various afflictions, including attacks by other Indian tribes and disease unwittingly brought in by the foreigners, the population of the Pecos Pueblo dwindled down to unsustainable numbers. The Pueblo was still occupied for the first 17 years or so of the Santa Fe Trail. In later years, wagon trains considered it a curiosity and camped nearby.

San Miguel

The river crossing at San Miguel was the perfect place for the fledgling government of Mexico to set up a "Port of Entry" for collecting taxes on goods coming into Mexico over the Santa Fe Trail. In the early years it was here that wagon trains were inventoried and taxes were collected.

Taxes levied on goods coming from the United States were an important source of income for the local economy. It has been claimed that the tax on wagon trains was the first source of revenue for the government of the newly independent country of Mexico.

Government officials eventually tired of having to inventory every item in every wagon, so they decided to tax each wagon $500, regardless of how much, or little, it contained. The traders bringing goods over the Trail were entrepreneurs in every sense of the word. It didn't take long before they started figuring out ways to pay the least tax possible. (A popular American pastime!)

The smaller, rugged, Missouri-built wagons were suddenly replaced by the monstrous "swaybacked" Conestoga freight wagons that are now the very symbol of the Santa Fe Trail. By bringing all your goods in one big wagon instead of several smaller ones, you could build a house with the savings in taxes.

The second thing that started was the practice of wagon burning. Each wagon left Missouri with crates and barrels containing two months worth of food and supplies for both teamster and livestock. Wagons were now just days away from Santa Fe, and those provisions were just about gone. By filling that empty space with cargo from other wagons, entire wagons in a wagon train could be eliminated altogether. To keep from having to pay taxes on the empty wagons, they simply burned them beside the Trail.

The practice of charging a flat $500 per wagon lasted only a few years so the practice of wagon burning subsided. One traveler on the Trail, though, wrote that the grizzled old veterans on the Trail enjoyed scaring newcomers as they happened upon the remains of these burned-out wagons. Instead of stories of tax evasion, these piles of ash and iron were offered as evidence of previous Indian attacks, terror and bloodshed.

Later the Port of Entry shifted upriver to San Jose. The town of San Miguel and its famous old church still thrive. It is enjoyable to explore San Jose, San Miguel, and then to continue on south to the gorgeous little "Villanueva State Park".

It is a pretty drive and you can even stop along the way to sample the wine which is grown and bottled locally. Vineyards in New Mexico? You bet. Four hundred years ago, Franciscan monks were using sacramental wines to conduct mass. It didn't take long to figure out that bringing wine from Spain was just too expensive and complicated, so vineyards were grown and wine was produced right here in the New World. Back in 1884, at almost a million gallons each year, the territory that is now New Mexico was the fifth largest wine producer in the United States.

Starvation Peak

Next on your journey along the Santa Fe Trail, to the south of the freeway you will see the tall but relatively small mesa called Starvation Peak. Legend has it that settlers were chased up the mountain and held there, surrounded by Indian warriors, until they succumbed to starvation. It was a prominent landmark and made for an interesting story around the campfire for Santa Fe Trail traders.

Hermit's Peak

The highest visible mountain west of Las Vegas is the round-topped Hermit's Peak. It is named after a colorful character that came to this region via the Santa Fe Trail and eventually called one of the caves home. Up close you will see that the east wall of Hermit's Peak is a sheer cliff. For those serious about hiking, the four-mile trail to the top offers a strenuous hiking opportunity amidst fantastic views. For those whose likes are not quite so intense, there are other trails in the vicinity which are not as grueling. Be sure to take along plenty of water.

Las Vegas

No doubt about it, Las Vegas was the stereotypical "Wild West" town. Las Vegas was famous for its gunfighters, saloons, shootouts, and hangings, but few know that Las Vegas was born for conflict. Las Vegas was established by Mexico to bear the brunt of the persistent raids by Plains Indians that had previously always plagued the town of San Miguel. But Indian raids weren't the only danger. Not long after Las Vegas was established, bandits like the Silva gang formed and terrorized the locals.

The arrival of Americans and the railroad didn't help matters; it brought a whole new generation of gunslingers, hoodlums, and ne'r-do-wells. At one time the town square had a windmill where more than one lynch mob strung up outlaws in "unscheduled" public hangings. In Las Vegas, Pat Garrett saved Billy the Kid from a midnight lynching by an angry crowd.

It is only fitting that a town with such tough men would one day provide 21 Rough Riders, many of whom rode with Theodore Roosevelt as he charged up San Juan Hill. But as tough a town as it was, Las Vegas also became a town of sophistication. Like a cross between Dodge City and Boston, Las Vegas had gunslingers in the saloons, and the upper crust of society in the opera house.

Visitors could stay in first class accommodations like Montezuma's Castle and yet could still drink in saloons and bars with the likes of Billy the Kid, Bat Masterson, and even Jessie James. Doc Holiday operated a dentist office, then a saloon and gambling hall in Las Vegas.

Las Vegas was like an oasis in the desert; it drew people with money and with influence, and the buildings they constructed show it. It had two first class opera houses, trolley cars in the streets and the first large-scale telephone system in the Southwest. Many of the buildings in Las Vegas were without rival west of the Mississippi. Even though many magnificent buildings have been lost, Las Vegas still has over 900 buildings on the National Historic Register, more than any other city in the United States.

The Santa Fe Trail went through the old original settlement, right through the plaza in the center of town. When the railroad came to town though, it shunned the Las Vegas town plaza and chose to build its own frontier version of town in the fields east of the existing Hispano settlement. Las Vegas has been divided ever since. Although both communities shared in the wealth, growth and history, they never became a united city. Even today, Las Vegas is like visiting two competing cities.

A combination of things ended Las Vegas's stint in the spotlight. Agriculture took a big hit during the Dust Bowl years. The Depression also contributed to Las Vegas's decline. But its ultimate downfall was the same thing that had originally built it: tourists riding the railroad. Interest in New Mexico dwindled as tourists' interest shifted toward California.

Casino owners and railroad officials saw their profits in Las Vegas dwindling as tourism shifted west, so a second "Las Vegas" was built in the deserts of Nevada. It too was built in an isolated area as a "stopover" for travel-weary tourists and it too was named "Las Vegas" hoping to capitalize on the reputation for glitz, glamour and gambling that made the original Las Vegas so profitable for them.

THE CIMARRON CUT OFF

Wagons on the Santa Fe Trail primarily followed one of two main routes. It has been estimated that as much as 75% of Santa Fe Trail traffic used the shortcut called the Cimarron Cutoff. As time went by the Mountain Route was developed, but the Cimarron Cutoff was the first "great trade route" connecting the fledgling nations of the United States and Mexico. Wagon trains traveling between Missouri and Santa Fe could make this crossing in 62 days.

The Cimarron Cutoff was harsh. In many places it lacked firewood, water and grass for the animals. As years went by, hostilities increased between wagon trains and some tribes of Plains Indians. The Cimarron Cutoff became increasingly deadly. Jeddediah Smith, a frontiersman famous for his exploits on the Oregon Trail, died on his very first attempt to cross the Cimarron Cutoff.

This route was all but abandoned in later years. Even in the beginning there was some apprehension and tension between the wagon trains and the Plains tribes, but the event that started the indiscriminate killing on the Santa Fe Trail occurred at a river crossing just north of Clayton at McNees Crossing.

McNees Crossing

The Santa Fe Trail did not necessarily blaze a new path; wagon trains crossed the whole prairie by traversing a complex web of centuries-old trails well worn by Plains Indians, Hispano buffalo hunters, and sometimes even buffalo herds themselves. Water was scarce through much of the prairie, so wagon trains followed the existing trails between watering holes and along rivers.

Members of the wagon trains would take turns acting as scouts and ride ahead of the wagon trains to determine which waterholes had water and to make certain that river crossings were passable. Early in the life of the Trail, two such scouts were sent to check out a river crossing where, as they napped, they were attacked by Comanches. John McNees died and was buried at the crossing, which was named after him. His partner, Daniel Munro, died several days later.

Those two deaths started a cycle of retaliatory killings by all sides which lasted for more than 40 years. McNees Crossing is just north of Clayton. It is a somber experience to stand in the Trail ruts on the west bank and look down over the rock-bottomed crossing. The usually dry river crossing is a great place to sit and reflect on the lives who made this crossing, and those who didn't. Appropriately enough, the east bank of the crossing sports a vivid array of wildflowers.

Land of Mesas

From Raton looking east the land is filled with many beautiful yet imposing formations which stretch all the way to Oklahoma. The tops of these mesas were ground level millions of years ago. It isn't hard to see why the Santa Fe Trail skirted around them. Traders felt that the hardships encountered going through Raton Pass were still easier than trying to take heavily-loaded wagons across these giants.

On top of Johnson Mesa, due east of Raton, you drive through miles of tall-grass cattle range and a graveyard of old abandoned homesteads, many deserted during the Dust Bowl years in the 1920s. Johnson's Mesa once had many homes, five schools and the first telephone lines in New Mexico. Now it is deserted except for cattle and a surprising array of wildlife. From the top you can see volcanic peaks rising up from both the mesa tops as well as the prairie floor below. Ages ago, this was an area of significant volcanic activity.

Capulin

East of Johnson Mesa, one of the better preserved volcanoes has been made into a National Park, the only one in the nation where you can drive up to the rim and hike down into an actual volcano. The Capulin Volcano is a real treat. Watch the movie in the Visitor's Center, peruse the books and exhibits, and then drive up to the top. From the top you can hike down into the core of the volcano, or if you are really enthusiastic, walk the 1-mile trail around the rim.

From the top of the Capulin Volcano, you can look out across the plains at all the lava flows and the remains of nearly 100 volcanoes that help define the horizon in this part of the state. These volcanoes weren't all active at the same time; nevertheless, it isn't hard to imagine what this landscape looked like in prehistoric times. Like stepping back in time, you can survey the same land that Folsom Man hunted. That's right; Stone Age man lived and hunted here.

Folsom Man

Humans were here as long ago as the Ice Age. Roughly 12,000 years ago you could well have witnessed the receding glaciers while an active volcano or two still spewed ash and lava into the atmosphere. Right here, you could have seen an occasional woolly mammoth as well as the ancient buffalo hunters pursuing the gigantic ancestor to our modern-day bison.

It was a long held belief that humans had only been on this continent for 3000 years or so, but a discovery just north of the Capulin Volcano, near the little town of Folsom, changed all that. Almost 80 years ago, a local cowboy discovered bones of a gigantic buffalo. Scientist studying those bones discovered that the animal didn't die of natural causes, but had been hunted and killed. Among the bones they found the spear tips used by . man, subsequently named the Folsom Man after the nearby town.

If you look to the northwest, from the rim of Capulin Volcano, you can see the area where the bones Folsom man's Bison were first discovered. If you drove across Johnson's Mesa to reach Capulin, you passed close to the area where erosion left the bones exposed.

Dinosaurs

Of course you can't talk of volcanoes, early man and the Ice Age without conjuring up images of dinosaurs. Well, we had those too. Over a hundred million years ago, this was the edge of what is now the Gulf of Mexico. Dinosaurs of many varieties roamed the muddy shores and their tracks have been preserved in the rocks.

At Clayton Lake State Park you can walk out among more than 500 different dinosaur tracks made by a variety of dinosaurs. The tracks left in the mud at Capulin are the biggest single collection of tracks in the area; however, we have over 100 known sites with dinosaur tracks, including one of the only confirmed T-Rex tracks known to exist anywhere. You can see a cast made from this T-Rex track at the Raton Museum.

Where the Buffalo roam and the Antelope play...

Indigenous people had hunted buffalo on these plains for thousands of years, but the reintroduction of horses by Spanish explorers signaled a big change for the buffalo. Indian, Spanish and Hispano hunters could now pursue buffalo hundreds of miles out onto the plains. Even without the assistance of saddles, warriors and hunters from Plains tribes became incredibly agile and acrobatic horsemen. Now suddenly, they could harvest enough buffalo to live on and still have surpluses enough to trade.

Santa Fe Trail travelers wrote of their excitement upon seeing a herd of buffalo. Buffalo were relatively easy to kill and provided fresh meat and enough jerky for the remainder of the two-month trip. Buffalo were not as common as you might expect, however. The average wagon train would only encounter buffalo once during a two-month journey. Buffalo had long been hunted out of most of New Mexico. To find buffalo in the 1800s you had to travel east of Clayton into what are now the plains of Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas.

The demise of the rest of the "free range" buffalo was inevitable as settlement moved into the prairie. Today, buffalo herds are contained by use of electric fences, but in the 1800s, buffalo went wherever they pleased. That made them disastrous to people trying to fence off land for farming or raising domestic livestock. The buffalo also provided life-giving support to the Native Americans. By eliminating the buffalo, the US Military could force warring Indian tribes into near starvation and ultimately bring about surrender. So, for a variety of reasons, the elimination of the free range buffalo was undertaken in earnest.

Buffalo hunting became a profession, and legends like Kit Carson and Buffalo Bill Cody could kill hundreds of buffalo in a single day. Buffalo hides were perfect for making the huge drive belts which the industrial revolution needed. After wagon trains sold all their goods in Santa Fe, the traders often bought mules to carry buffalo hides back to Missouri.

Beef

As Plains tribes acquiesced to the westward expansion of the Americans, reservations were established and Indian Agencies were set up all over the West to distribute the agreed -upon rations to Native Americans. This meant providing grains and flour, but more importantly, it meant replacing the buffalo meat with beef. This triggered the real beginning of the cowboy era in New Mexico.

As you cross the prairie between Springer and Clayton, you are crossing what could well be dubbed “Cattle Drive Alley”, where fortunes were made and lost rounding up wild strays in Texas and driving them north to market. Some of those cattle drives just passed through here headed as far north as Wyoming. Others were destined for local Indian Agencies or to supply Fort Union.

Cattle drives also made their way to present-day Clayton for shipment on the newly built railroad. More than a hundred years later, cattle still outnumber residents; many times over. Clayton continues to be a major cattle market with huge industrial-style feedlots and still serves as a railroad shipping point for beef raised throughout the surrounding region.

Outlaws

Modern-day movies like to make outlaws look romantic, but in the old days, they took horse thieves and train robbers seriously. Black Jack Ketchum was a ruthless murderer and train robber who occasionally rode with Butch Cassidy's Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. After robbing a train for the third time near Folsom, the notorious "Black Jack" Ketchum was injured and captured.

After his trial he was hanged in Clayton. At the Herzstein Memorial Museum in Clayton, you can get the whole story and they even have photographs of the gruesome event. There you will find interesting exhibits and a delightful curator with many insightful stories of the era.

Scenery

Much of the beauty in this portion of New Mexico is subtle. These are called the High Plains, because even though they are the rolling grasslands of the prairie, the elevation is actually quite high. In many places here the prairie floor is 1000 feet higher than the "Mile High City" of Denver, Colorado. Out on the prairie, the low horizons make for big skies, incredible sunsets, impressive clouds, and lots of sunshine. The distant peaks of mountains and volcanoes add an accent to an otherwise plain prairie. This area still has many of the old wooden windmills, some of them very old, which still pump the water necessary to support life.

The Plains may look desolate, but there is plenty of life. In spite of appearances, there are trees; lots of them. The trees in this country are somewhat subterranean; they grow below the surface of the windswept prairie in the ravines, arroyos and washes that cut thousands of swaths through the land. Clayton Lake is a beautiful example with deep blue water, surrounded by rugged rock cliffs and green trees of all sorts, but it is all contented to rest completely out of sight from the prairie floor.

At various times of the year, these lands sprout an amazing variety and intensity of wildflowers. Wildlife is diverse, but you have to really look to see it. Hawks love to use fence posts or telephone poles to perch up high so they can keep a sharp eye out for rodents of all sorts. Elk, deer, antelope, bear, bobcat, mountain lion, coyotes, plus birds, rodents and reptiles of all sorts can be found here.

Santa Fe Trail Museum - Springer

Springer was primarily a railroad town. Today it hosts an officially designated "Santa Fe Trail" Museum that has a great Santa Fe Trail Interpretive Center. It is housed in the old courthouse which once served as the county seat, and sits right in the middle of town.

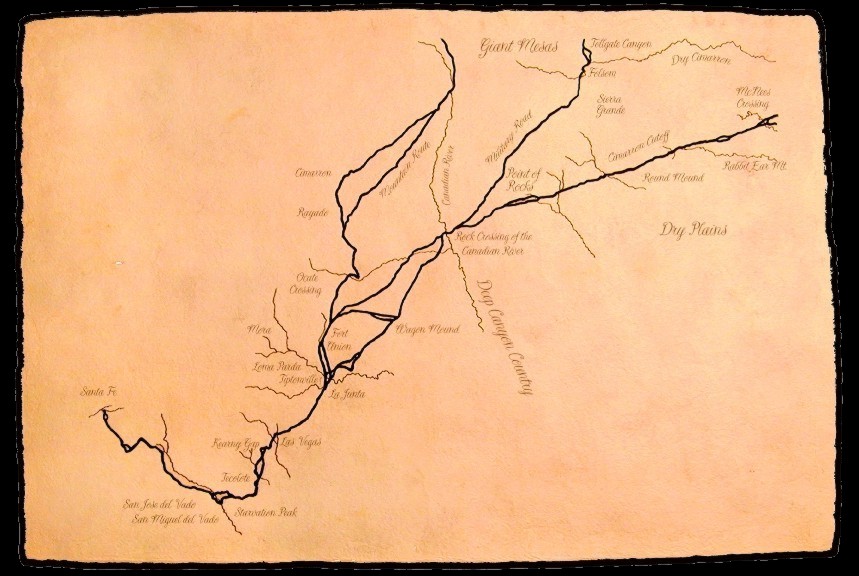

Alternate Routes

The Santa Fe Trail is actually not one single trail, but more like a corridor where many trails wove their way across the plains. Wagon trains are usually depicted as a long line of wagons running single file. In reality, they often traveled in four columns. Santa Fe Trail ruts often run three or four abreast. Wagon trains also made new shortcuts as conditions and water dictated, or where an advantage might be gained. Shortcuts and lesser known routes of the Santa Fe Trail are indicated on the map. The Granada - Fort Union Military Freight Road was used for only a couple of years before the end of the Santa Fe Trail era, and then, almost exclusively by military freighters. The Aubry Cutoff didn't go through New Mexico, but some wagons deviated from that cutoff and made their way into New Mexico following the Dry Cimarron River. Many of the communities around Folsom were settled by people who initially traveled this shortcut.

Landmarks Along the Trail (from East to West)

Rabbit Ears - Visible just north of Clayton, these twin peaks are the easternmost of a series of Santa Fe Trail landmarks in New Mexico. For Santa Fe Trail travelers coming west, after spending nearly a month looking at nothing but endless oceans of grassland, it was a welcome landmark and an indication that the end of the prairie portion of the trip was near.

Round Mound - The next landmark in the series was Round Mound, just one of the many volcanic remains on this prairie floor. The view from the top is awe-inspiring. Unfortunately, like many of the landmarks along the Trail, it is on private land and not easily accessed. Today it is called Mount Clayton.

Point of Rocks - Travelers on the Santa Fe Trail used the Point of Rocks for navigation. It also became a popular place for wagon trains to camp because of the water from the natural spring and the availability of wood for campfires. Unfortunately, it was a popular place for ambushes by Indians. There are numerous teepee rings and eleven Santa Fe Trail-era graves here.

Dorsey Mansion - The Dorsey Mansion is not a Santa Fe Trail relic but nonetheless played an interesting role in the history of the area. Built in the 1800s, Dorsey's ranch was eventually eight miles wide and sixty miles long with more than 50,000 animals. The Mansion is a 10,000 square foot building, half of it built like a log cabin and the other half built like a stone castle. It has real gargoyles and the Southwest's oldest greenhouse.

Rock Crossing of the Canadian River - It was difficult to take a heavily loaded freight wagon across a river. The Canadian River was especially difficult because it either flowed through deep rock canyons, or over very sandy soil. The "rock crossing" was the ideal place for wagons to cross the Canadian River, and most all the variations of trails converged so they could cross the river where it flowed over this solid slab of rock.

Wagon Mound - One of the significant landmarks on the Santa Fe Trail, Wagon Mound is as popular with travelers today as it was during Trail days. To people in wagon trains coming from Missouri, Wagon Mound meant they were roughly 100 miles from Santa Fe. It had to be a little bit of a fearful sight as well, though, because the mountain had a reputation for providing Apaches, Utes and Comanches with a good location to ambush wagon trains and stagecoaches. Eleven people escorting a stagecoach carrying the US Mail were ambushed here. It is surmised that the little community graveyard at the northern base of the mountain was started with the graves of these unfortunate travelers.